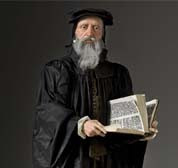

This Week in Church History: John Knox, Scottish Reformation

On November 24, 1572, Scottish reformer John Knox died in Edinburgh.

Born in 1514, Knox trained for the priesthood and was converted under George Wishart, an early martyr of the Scottish Reformation. While pastoring in St. Andrews, Knox was imprisoned after Wishart's death and served for 19 months as a galley slave. After his release he pastored in England until Mary Tudor ascended the throne, when he escaped to the continent, where he studied under John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger. Knox described Geneva as "the most perfect school of Christ on earth since the apostles," and during his exile he developed his defense for rebellion against idolatrous magistrates and female sovereigns. Upon his return to Scotland in 1559 he led in the development of the Scottish Reformed Church, introducing Reformed worship in his Forme of Prayers and Presbyterian polity in his Book of Discipline. In addition, his Scottish Confession, approved by the Scottish Parliament in 1560, was the confession standard of the Church of Scotland until it was superceded by the Westminster Standards in 1647.

Knox's secretary, Richart Bannatyne, recorded the passing of the "Thundering Scot" with these archaic words (recorded in the Presbyterian Guardian, November 4, 1935):

On this manner departed this man of God, the lycht of Scotland, the comfort of the kirk within the same, the mirror of godliness, and patrone and example of all true ministeris, in puritie of lyfe, soundness in doctrine, and bauldness in reproving of wickitness, and one that cared not the favor of men (how great soever they were), to reprove their abuses and synis. In him was sic a myghtie spreit of judgement and wisdome, that the truble never came to the kirk sen his entering in publict preiching but he foirsaw the end thereof, so that he was ever reddie a trew counsall and a faythfull to teich men that wald be taught to tak' the best and leive the worst.

Labels: History